Report | January 7 2026

Muhammad Ali Pate, Donald Kaberuka, Peter Piot

Muhammad Ali Pate (1), Donald Kaberuka (2), Peter Piot (3)

1) Coordinating Minister of Health and Welfare, Nigeria; 2) High Representative for Financing the Union, African Union; Former President African Development Bank; 3) London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Former Executive Director, UNAIDS

Note: a shorter version of this paper was published in Think Global Health

The past 25 years have seen extraordinary progress in health outcomes in low and middle income countries thanks to a combination of leadership, innovation, and domestic and international funding. A complex and vast set of global health institutions (GHIs) emerged at the same time and were instrumental in driving this progress.

However, the global health ecosystem now finds itself in crisis, as a sudden drop in donor funding threatens to unravel decades of hard-won progress. Furthermore, persistent and longstanding deficiencies continue to pervade the global health system, marked by a fragmented landscape of institutions, limited local ownership, inefficiencies, underinvestment in health systems, and a reliance on donor funding. A much needed paradigm shift is for health to be reframed as a core development priority, with GHIs repositioned primarily as catalysts. By acknowledging both the strengths and flaws of the current ecosystem, we call for practical yet deep reform, using 6 basic principles:

1. Reframe health as a core national development and infrastructure priority.

2. Country-driven priorities: GHIs should be positioned as instruments supporting and catalysing nationally defined and regionally agreed priorities. Regional entities are well placed to shape priorities, but a clear division of labour is needed.

3. Efficiency and equity: Reform must generate better value for money, reduce the administrative burden, and redefine return on investment in terms of health outcomes, system performance, affordable innovation, and sustainability. Expertise is now available in most countries, who need fewer foreign consultants.

4. Preserve global public goods: International funding for global public goods and against global threats should be strengthened. These include data, norms and standards, R&D, access, pooled procurement, and epidemic preparedness.

5. Institutional excellence and accountability: Organisations must be assessed for capacity, critical mass, and adequate human and financial resources. Sunset clauses should be considered .

6. Complementary financing: International funding should complement domestic investment and support a transition pathway for heavily debt burdened countries

We review the potential implications for GHIs, from multilateral organisations, funds and banks to disease specific entities, and product development partnerships). We call for a sharp strategic focus, inclusive and equitable agenda-setting, and more efficient delivery mechanisms. This includes harmonizing planning and reporting, and reducing the number of institutions through consolidation. Where feasible, staffing and major functions should be relocated close to partner countries.

Change carries substantial costs and risks, chief among them a reduction in funding.

We therefore suggest a series of steps to advance the reform agenda:

1. Be proactive, and do not assume a resumption of past international donor funding levels.

2. Co-create reform with key constituencies, connect with emerging initiatives, embrace leadership from the Global South (e.g. the Accra Reset), and move away from overly academic proposals to concrete political and institutional action.

3. Define clear timelines for action. Use 2026 for strategy and planning, and aim for implementation by 2027 and 2028.

4. Consider carefully legitimacy and governance: “Coalitions of the willing”, are likely to be more effective than solely relying on donors or individual governing boards of the institutions concerned.

5. Prioritise realistically and capitalise on any momentum for change, rather than trying to change the whole ecosystem at once.

6. Establish domestic investment in health as a national development priority, funded by domestic revenues and development banks, with development assistance for health (DAH) reserved for the transition and global public goods.

7. Ensure continuity of essential services, especially in humanitarian and epidemic crises, and disease prevention.

8. Balance trade-offs: while consolidation and domestic efforts are important, international support remains vital for areas such as emergency response, innovation, and biosecurity.

9. Engage constituencies, as GHIs have committed supporters. Reform efforts must engage with them, whilst avoiding being derailed by vested interests.

10. Consider simultaneously the role and possible reforms of regional institutions, and the balance between global and regional approaches.

Rather than focusing on the risks and challenges, emphasis should be placed on seizing opportunities. Within the next 3 years, a transformed ecosystem should be in place; one that re-energises global health efforts, builds more resilient, equitable and sustainable health systems to better serve all populations, especially the most vulnerable.

The past 25 years have seen extraordinary progress in health outcomes across most of the world. A thriving global health ecosystem emerged - including significant financing programmes, disease specific initiatives, and product development partnerships (PDPs). This was largely driven by a combination of domestic investment and soaring levels of public and philanthropic funding from high income countries. But this ecosystem is now in crisis, with hard won gains at risk because of an abrupt decline in donor funding.

Despite the extraordinary successes of the global health system, the need for reform has been a long time coming. There has been a growing and vocal demand from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), as well as from donors, for a paradigm shift in international funding practices. This momentum was evident at the Accra Summit on Africa Health Sovereignty in August 2025 and the launch by President John Mahama of Ghana of the ‘Accra Reset’ at the 2025 UN General Assembly – a bold new framework to help re-imagine governance architecture for global health and development for the post-SDG era (1,2).

In the spirit of this drive for reform, this forward-looking paper reviews the core challenges and opportunities for optimizing the global health ecosystem to improve health and development outcomes across the world. Let us be clear: retaining the status quo is not an option. A short-term “crisis management” response, will not be sufficient. Expecting a return to the early 2000s levels of international funding severely underestimates the profound paradigm change that is now underway. We must look to the future. We must seize this moment to fundamentally realign systems and priorities to make global health institutions more relevant, equitable, and more effective for tackling the health challenges of the next 25 years.

In the year 2000, more than 10 million children around the world died every year. This number is down to fewer than five million children despite a concurrent population growth of 30% (3). In the same period, the incidence of the world's deadliest infectious diseases fell by half. Progress was seen in regions with the highest disease burden, with Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia showing the greatest improvement (4)

Starting from around the turn of the millennium, as awareness about the devastating HIV pandemic, high child mortality rates and the collective benefits of better health worldwide grew, the world's wealthiest countries began steadily increasing their funding to supplement low-income countries’ financing. This was largely driven by a concerted global health movement – particularly around HIV/AIDS - and new philanthropic initiatives such as the Gates Foundation. Domestic leadership and funding also played a key role, as well as access to affordable health innovations, such as new vaccines, dual insecticide impregnated bed nets against malaria, and lifesaving new HIV treatment.

Whilst the World Health Organisation (WHO) - the principal multilateral body for global health- had already been in existence for over a half a century, the proliferation of new global heath institutions (GHIs) at the turn of the Millenium, was largely driven by funders requesting new channels, political momentum, frustration with the effectiveness of existing institutions, and a keen interest in health innovation and access to new tools. This sometimes resulted in new and distinct delivery channels. For example, at that time separate supply chains were critical for ensuring access to antiretrovirals against HIV whilst today there is a strong case and growing capacity for integrated, national supply and delivery systems.

In total, it is estimated that the world invested more than $880 billion in development assistance for health (DAH) DAH from 1990-2019, with 80% of those funds invested after 2000, focussing mainly on HIV/AIDS, TB, malaria, and vaccines for children under five (5). For most LMICs and particularly in Africa, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (The Global Fund) and the largest ever American bilateral programme, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), have been the biggest sources of external funding for health, followed by Gavi and then the World Bank. Between them, these typically represent over 80% of DAH, with the remainder coming from a wide assortment of multilateral agencies, bilateral donors, and private philanthropy. This funding has been instrumental in driving down the rate of deaths from HIV/AIDS by nearly two-thirds since 2003 (3,4) amongst other major successes. The current funding reductions to these programs and institutions will unavoidably reverse many hard-won gains in health and lives saved.(6)

Several country experiences point to how development assistance for health (DAH) can align with national priorities and strengthen health systems whilst also improving targeted outcomes. For example, Rwanda used DAH pooled with national reforms (including a community-based health insurance scheme, performance-based financing, and a community health workers program) to strengthen primary care and reduce maternal and child mortality. Similarly in Ethiopia, DAH channelled through the Health Extension Program (HEP) supported a government-led primary care platform and brought down child and maternal deaths. In both countries, Global Fund and PEPFAR support was integrated into national systems for HIV, TB and malaria, supporting labs construction, supply chains and community platforms and contributing to sharp declines in deaths.

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) have also been quietly driving gains attributed to the global health movement by investing both in health and in supporting wider infrastructure, education and social protection programs. For example between 2005 and 2016 the World Bank Group committed about $23 billion in financing health services (7). This was alongside concessional water and sanitation lending averaging roughly US$0.6 billion per year - around half of which was for Africa. As will be discussed later, the role of MDBs will likely be even more central in a future with lower levels of DAH.

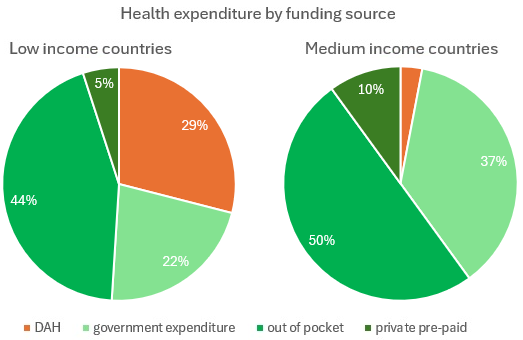

Despite all the successes, it is critical to keep the role of DAH funding in context (5). According to a study by the Center for Healthy Development (8), DAH represents a vital but modest share of the total health expenditures in low-income countries (LICs) and an even smaller share in middle-income countries (MICs) where the majority of the world’s poor live (see Figure 1). In 2019, 44% of health expenditure per capita in LICs was “out of pocket”, 22% was government expenditure for health, while 29% of the health expenditure came from DAH. In MICs, only 3% of health expenditure is sourced from DAH. Whilst progress on health in LMICs has been driven by domestic funding and action, international funding has been playing a much larger role in disease-specific programs and health gains, in particular HIV, TB, malaria and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). and importantly often with earmarked funding for marginalised populations. Without such international funding the major progress in these areas would probably not have happened.

Figure 1. Health expenditure by funding source (based on reference 8)

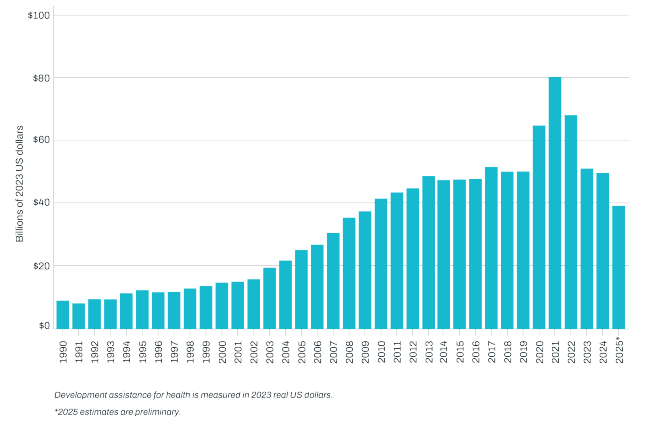

Preliminary estimates of development assistance for health, showed that DAH dropped by 21% between 2024 and 2025 from $49.6 billion to $39.1 billion (Figure 2). Forecasts from IHME indicate that development assistance for health is likely to further decline over the next five years, to $36.2 billion in 2030 (6) - which in our view is rather optimistic.

Figure 2: Development assistance for health, 1990-2025 (source: IHME, reference 5)

While recognising the many success stories, DAH – both multilateral, and particularly bilateral – has also often had unintended negative consequences (9-12), including:

Countries receiving multilateral and bilateral DAH have become more vocal about the need for more efficient support, respect for national priorities, and health system strengthening and there have been several recent attempts for reform for GHIs, such as the 2023 Lusaka Agenda (14). At the regional level, in Africa for example, the 2019 African Leadership Meeting (ALM) on Investing in Health called for greater sovereignty in health financing, and a rebalancing of the relationship between African governments and global health initiatives (15). The 2022 African Heads of State and Government formally backed Africa’s New Public Health Order in a Call to Action (16). This momentum was further reinforced at the Accra Summit on Africa Health Sovereignty in August 2025 resulting in the high level Accra Reset Initiative (1).

The need for “radical reform”, is also being advocated by donors and leadership at GHIs including both the CEO of Gavi, Sonia Nishtar (17) and of the Global Fund, Peter Sands (18), who, to different degrees, are proposing a series of major structural reforms and news way of working.

Change is also an imperative because of the need to address profound shifts in disease patterns, including a tsunami of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). There are substantial demographic changes at play with greater longevity and declining fertility rates in most countries, and continuing population growth in others, particularly in West and Central Africa, all against a backdrop of climate stresses. Half the world is still lacking access to basic healthcare, with the goal of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) still far away. Furthermore, trust in science, governments, and institutions, has continued to decline and is often fuelled by a deliberate use of misinformation.

Encouragingly, there remains significant potential for progress driven by innovation. Academic and public health centres of excellence and innovation are now no longer limited to HICs, and the accelerating digital and AI revolution offers opportunities for leapfrogging in health. Declining funding, however, puts the potential benefits of such innovation at risk.

New technologies may also generate new demands for global and regional market shaping, and there will always be a need to counter the threats of infectious disease and pandemics, where global collaboration will remain paramount.

We do not discount the risks of undertaking widespread reforms. In the first place, international funding for major disease specific causes could continue to decline, and may not be redirected to health system strengthening, sustaining health gains, or addressing new health challenges such as chronic conditions. The risk is also high for a decline in much needed humanitarian crisis aid. Paradoxically, there may be less domestic commitment to health in the absence of international incentives, including programmes benefiting marginalised communities, such as populations affected by HIV infection. Research and innovation relevant for advancing health in LICs may also be negatively affected.

Costs of any institutional reform can be high, and major consolidation may actually reinforce the dominance of the Global North if not accompanied by significant other changes as proposed here. Finally, there will undoubtedly be resistance to change from both within the organisations, activists, and other vested interests, and it is not unusual that the same donor has different positions in different boards. Communication and early engagement will be essential, besides strong leadership, both within the system and among funders.

Before exploring the details of any reform, it is critical to state that part of a much-needed paradigm shift is to view health as an outcome of strategic choices in health interventions, infrastructure, education, jobs, digital systems, governance, R&D and manufacturing (such as Nigeria’s Presidential Initiative for Unlocking the Healthcare Value Chain). Health must be positioned as a core macroeconomic and development priority, financed primarily by domestic revenues and supported, where needed, by development banks (including the Africa Development Bank, the World Bank, and others). Global health institutions must be repositioned primarily as catalysts rather than the centre of gravity, with NGOs, philanthropy and other parts of the global health ecosystem aligning behind national driven priorities, as well as wider global public goods. Innovation – including in the transition from analogue to digital and AI enabled systems- needs to happen within those nationally owned frameworks. Critically, we see global health institutions as playing a key role in market shaping (establishing norms and standards, creating market incentives and mobilising financing) and also supporting local manufacturing to further support sovereignty and resilience in health systems.

Any reform should be guided by present and future goals for improving health outcomes, rather than by institutional interests. We realise that in practice, some compromises will be needed in the transition – provided that they lead to meaningful change, not superficial fixes.

In the past there have been several initiatives and commissions, usually donor driven, which have set out to increase coordination and coherence across multilateral and bilateral agencies, and reduce the burden on countries. They rarely led to meaningful change, did not address structural issues, and often resulted in an additional layer of coordination bodies. (e.g. UNAIDS “3 Ones”, IHP+, SDG3 Global Action Plan).

We suggest 6 broad principles for transforming the ecosystem:

1. Reframe health as a core national development and infrastructure priority (see above).

2. Country-driven priorities. The principle of subsidiarity between the global level, regions and countries should be considered for a number of global health functions, including normative guidance and technical support. The emergence of regional and national centres of excellence in health has been a sea change in the past 25 years, with technically and politically strong regional organisations like the new Africa CDC and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), over a century old), as well as academic centres. These are in a better position to ensure that priorities are shaped by those closest to the challenges and the solutions, but there will also be a need for a clear division of labour among regional institutions.

3. Efficiency and equity: It is essential that any reform delivers better value for money and greater equity, is results driven, and reduces the procedural and administrative burden on countries. This could involve supporting innovation in tools and delivery, providing temporary supplemental funding, and investing in the development of a superior health data infrastructure. Without a greater return on investment (ROI) through simplification of processes, focus, and consolidation, and more local and less costly implementers, there is no point to invest the considerable energy and costs of reform. It is key to re-define ROI in terms of at least four achievements: 1) better health outcomes; 2) performing and efficient health systems; 3) affordable and effective innovation; 4) financial and societal sustainability.

4. Preserve global public goods: International funding will remain essential in functions related to global public goods and global common threats, and should even be strengthened as there is much needed value added of transnational collaboration. These include health data and surveillance; normative and standard setting guidance; research and development, innovation and equitable access; market shaping through aggregated and predictable demand, and pooled procurement; rapid response infrastructure, and mechanisms to respond to global common threats (e.g. humanitarian assistance, epidemic preparedness). However, these functions, as well as the knowledge system and R&D agenda, should be rebalanced to take more into account priorities beyond those of HICs. Here we see a greater role for regional bodies than is the case until now. Furthermore, we urge a shift away from the sometimes default use of costly international consultants to instead prioritise local and regional expertise.

5. Institutional excellence and accountability: A professional assessment of the capacity and quality of existing institutions to achieve their mission should equally inform any reform. Key questions are whether an organisation has the needed critical mass, minimal financial resources, quality human resources, up-to-date knowledge and data management systems, and relevant stakeholder engagement. Maintaining relevance over time in ever changing contexts is rarely applied in international organisations. A review of existing GHIs can identify the time for a sunset clause where appropriate.

6. Complementary financing: International funding should consistently be complementary to domestic investment. Where the public financial management capacities are sufficiently robust, this would preferably be pooled for sector wide approaches, and committed over enough time to ensure a lasting impact. So-called “aid at the margin” as proposed by the Centre for Global Development could futureproof international financial flows (19). At the same time, domestic health funding should increase nearly everywhere, while recognising the growing debt burden in many countries (20, 21). There is a need to improve the international finance system, embrace innovative financing mechanisms, and give developing countries fair terms and the ability to grow economically. A discussion on this crucial challenge is beyond the scope of this paper.

Mergers and acquisitions?

An obvious option is a reduction of the number of global institutions to increase efficiency and reduce the procedural burden on countries, through mergers or absorption of smaller entities into larger ones. Such consolidation can be beneficial when organizations develop positive synergies under one “roof”, which is frequently carried out in the private sector. However, consolidation should not be the goal of reform, but only a potential means to achieve better outcomes. Mergers are always a challenge, and carry financial, human and operational costs in the short term. They should only be considered where the strategic objectives, mission, and values of the organizations are clearly aligned.

Back-office functions such as human resources, legal, finance, and communications can be consolidated, while procurement, outreach, and country offices could be combined in entities that pursue similar activities. This might be particularly relevant for product development partnerships and financing institutions.

There are many examples of successful (and also failed!) mergers and acquisitions in the private sector, but less so in the public or NGO sectors – if only because there have been fewer attempts. A recent merger in the international NGO sphere is the HealthXPartners holding including PSI and the Elisabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, and on the multilateral side the Bioversity-CIAT Alliance, established in 2019. Major international NGOs such as Save the Children, Mercy Corps, and CARE pool their surge capacity for disasters. In addition there is the serious challenge to tackle the complexity created by the many smaller, including bilateral, funders, and the subsequent burden on countries, for sometimes modest contributions (for example Malawi is benefitting from the support of nearly 30 bilateral donors, and nearly 20 various multilaterals…).

Finally, limited or “optics focussed” reforms can be just as expensive and time consuming as more structural transformations, and should be avoided as the benefits are marginal at best.

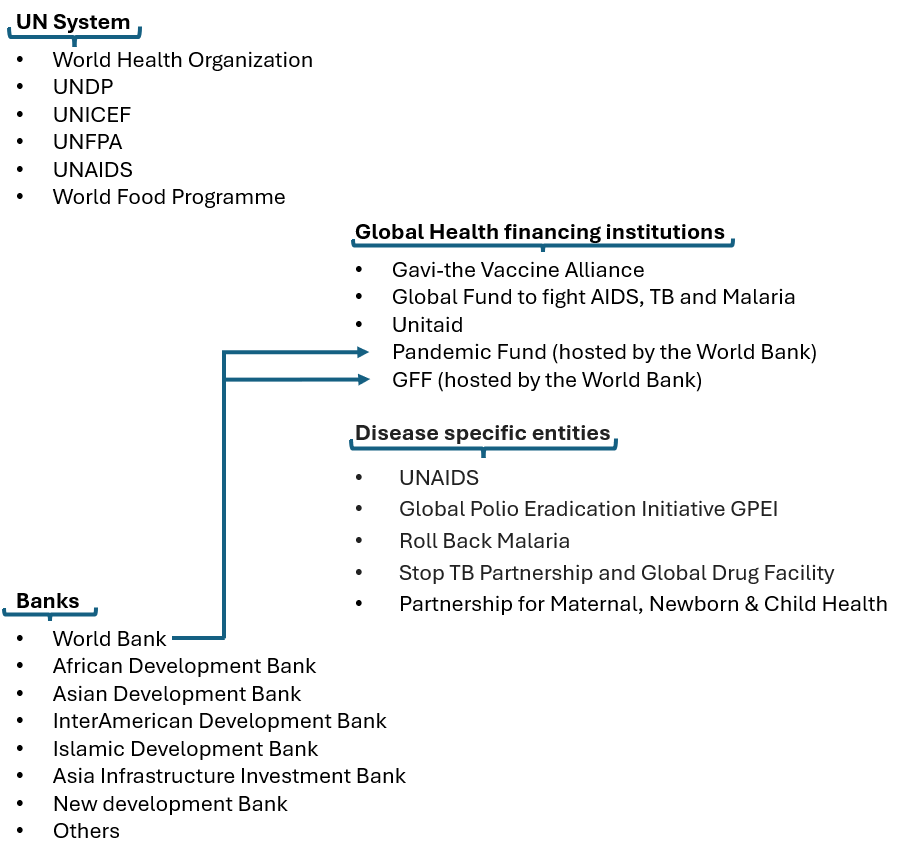

What does all this mean for the various types of GHIs? We recognise that each substantive global health issue, and each institution, requires in depth reviews beyond the scope of our viewpoint. It is important to see these proposals in the context of a much wider movement of reform of the entire multilateral system, involving hundreds of organisations as recently proposed by Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’ UN80 initiative (22).

As a contribution to current debates, we highlight below some specific reform options, based on what we believe are rational approaches to change, whilst also realising that ultimately compromises may be needed.

In general, the goal should be an ecosystem with fewer institutions, with a critical mass of human and financial resources, stable funding, and connected to the countries they serve in an equitable way.

Figure 3. Key multilateral global health institutions

The overall priority for the various UN agencies is to refocus sharply on their core mandates. We will only briefly discuss WHO, an intergovernmental agency unlike other global health institutions.

The World Health Organisation is at the core of the multilateral health system with a complex governance. It is in the midst of restructuring due to financial shortfalls, and there are plenty of suggestions for reform.

In addition to a need to reform WHO’s funding model, and governance (23), we suggest a resolute re-focus on WHO’s core mandate around global public goods, including an irreplaceable normative and standard setting role; health data, intelligence, and surveillance; epidemic preparedness and response; and convening power.

Technical assistance should focus on global goods, health financing, health policy, the organisation of health systems, though mainly through brokering, rather than directly delivering services. It also implies revisiting the role, number and size of national (and certainly sub-national) offices, except in countries in crisis. A detailed discussion of the role of WHO’s regional offices, and their relationship to other regional bodies is beyond the scope of this paper.

A focus on these core functions also implies that WHO stops or adapts certain activities it currently assumes, such as the conduct of research, procurement, engagement in manufacturing, and operational interventions. This should include humanitarian crises or epidemics, where their key role is policy guidance, data management, coordination, and facilitating technical assistance – however the reality is that member states can request operational support in crises.

As an illustration of the re-focus, WHO would continue to have a key role in setting research priorities, monitoring technology developments, and guidelines, while addressing the implications of innovation. Similarly, in terms of the important regulatory role of “prequalification” (PQ) of vaccines, medicines and diagnostics, the core focus of WHO should be setting norms and standards for regulatory quality, convening regulatory bodies, and the maintenance of a reference database of approved products. Ultimately, national and regional regulators should take on the roles of approving products. While an alternative system for the important prequalification function is developed over the next few years, regulatory bodies such as the African Medicines Agency and upgraded national regulatory authorities should lead to a system involving the major regulatory bodies.

UNICEF, UNFPA, WFP, UNDP: Each of these play critical roles in health (and are co-sponsors of UNAIDS) but also have major mandates beyond health. The UN80 report by the UN Secretary-General proposes a number of structural efficiency gains and mandate re-focus, for example in procurement and humanitarian crises (22).

In addition to these, we recommend a review of the UN system’s human resources or staffing model. UN staff are not only highly expensive, but appointments are subject to considerable political involvement, and performance management remains highly restrictive and often without consequences in case of poor performance.

The Global Fund and Gavi(together with the bilateral US PEPFAR) have each made huge contributions to the considerable progress on many health outcomes, with a dominant funding role in many low-income countries (3-5). For the foreseeable future, they will remain necessary to support immunisation, and HIV, TB and malaria programmes in the poorest countries. However, there are increasing concerns about inefficiencies, burden on countries, ways of working, equitable governance, and above all, the likelihood of reduced donor support over the next decade – even if the 2025 Gavi and GFATM replenishments were deemed a relative success.

There is a strong rationale for a degree of consolidation of both institutions– lower cost to implementing countries; operational efficiencies; optimized governance and policy; greater leverage for market shaping and joint fund raising.

A holding company with single governance and secretariat, with two operational entities, but with harmonized funding, granting, and monitoring and evaluation cycles and processes is a logical model. This could also host the Pandemic Fund, Unitaid, and the Global Drug Facility for TB. The expensive Geneva presence should be minimized to where there is value added to be close to UN and WHO headquarters.

There have been encouraging statements by the leadership of both organisations on the need for some form of consolidation (17,18), and upcoming governance and leadership changes may create opportunities. In addition, they have already established common project management units in at least 13 countries.

Any change will not be without risk. In particular, a reduction in combined donor funding, and a slowing down in delivery during a transition period. However, in our view, the risks of the counter factual (i.e. no change) are higher. The process for the first steps of consolidation can start in 2026.

Unitaid was established as a predominantly French initiative in 2006 when the Global Fund was already fully operational, as an innovative mechanism financed through levies such as the airline ticket tax, though in practice most of its resources have come from a narrow group of donors. Unitaid’s main comparative advantage has been to accelerate country introductions of innovations, albeit with a small budget ($32 Million in 2024). It is headquartered in the same building as GAVI and GFATM in Geneva, though hosted by WHO. The same arguments as above are valid for Unitaid, and one option is a merger with the new GAVI/GFATM holding company, with a mandate to promote innovation. An alternative could be to become part of a holding consortium of upstream PDPs. The risk is slower uptake of innovation.

The Pandemic Fund (PF) is a multilateral financing mechanism established following the Covid pandemic, dedicated exclusively to pandemic preparedness. Over 40% of its funding is allocated to African countries, with obligatory domestic co-funding, though only through other international institutions as intermediaries, making other GHIs and UN entities major beneficiaries.

There will be a continuing need to support pandemic preparedness and prevention. The question is whether a separate entity with its own rules and administration remains the most cost-effective option, and we suggest that being part of a large financing institution such as a GFATM/Gavi holding is a more cost-effective option. The Fund was originally created for an 8-year life span, when a thorough assessment will be needed, if not sooner.

A sunset date can be decided for each by the governance for all entities. However as stated earlier, there will be a continuing need to fund infectious disease threats and immunisation for low-income countries. This may be taken on by either the consolidated institution, or a new entity.

MDBs are major players in various aspects of country budgets, and before the major rise in DAH around the Millenium, they were regularly a source of funding in health, mostly through concessional loans. Their role in health financing is likely to become again more important. For example, The African Development Bank has a dedicated $6 billion plan for health infrastructure and pharmaceutical manufacturing, and now approves about $11 billion a year in new operations across energy, transport, agriculture and social sectors. It is up to countries to decide whether to borrow for pooled multilateral finance such as IDA and other conditional loan mechanisms.

Equally important is that the World Bank and other MDBs, and GHIs much better align their procedures and programmes, as today they can be disconnected, creating more and expensive inefficiencies.

A distinctive aspect of the Global Financing Facility for Women, Children, Adolescents (GFF) is that it leverages World Bank IDA, is largely country-led, and is supporting health services not tied specifically to diseases and vaccines. Its performance is strong but its current contribution is relatively modest. GFF can become a financing incentive instrument for health systems and primary health care.

Several MDBs were already going through internal reforms from before the current global health financing crisis, and the G20 has called for serious MDB reform, with increased funding (including for health), and greater engagement with national governments and private sector. In June 2025 in Paris, MDBs committed to increase country level collaboration and local currency lending. More recent actors in the global health field are the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the New Bank, the European Development Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development – with Nigeria becoming a shareholder.

Besides traditional lending, innovative financing and co-investment beyond the classic donor-recipient model should be able to unlock blended finance for health infrastructure, digital systems, and innovations. Any reform should in addition take into account the macro-economic environment, debt, fiscal space.

Around the Millenium, a number of disease specific entities were created to accelerate the response to major infectious disease threats. At times of reduced resources, a clear need for better integration and more system strengthening, such separate entities are hard to justify. They can achieve their missions if included in larger organisations or grouped together, as long as there are specific human and financial resources for their mission.

UNAIDS: As of 1995 UNAIDS played a major role to put a devastating epidemic on the global political agenda, mobilise funds, support country programmes, and enable access to life saving medication in LICs which shouldered the highest disease burden. It also brought together up to 10 UN system agencies around one issue. However, its funding is now collapsing. In recent years it has expanded advocacy beyond HIV to a number of topics owned by other UN agencies, and is often no longer operating as a joint UN programme. Closure of UNAIDS as early as end 2026 is proposed by UN80 (22). Its normative and data reference function, and country support can then move to WHO, whereas crucial civil society activities can be assumed by UNDP, and possibly the Global Fund. A major risk is the decline of HIV advocacy and action, in particularly for civil society, and programmes benefitting the most vulnerable and “key” populations. Establishing global and regional civil society platforms for HIV advocacy and civil society should be considered.

Global Polio Eradication Initiative GPEI: This is not a legal entity, but a crucial coordinating body governing the crucial polio eradication efforts through a partnership, overseeing a large annual budget ($6.9 billion for 2022-2029). An obvious sunset clause is when polio will be eradicated, with the most logical option being hosted by Gavi, possibly at the end of its current strategy in 2029, if not before.

Roll Back Malaria, a partnership established in 1998, has been an important advocate for malaria elimination working closely with other malaria advocacy entities1 . Such advocacy will remain crucial for the foreseeable future but can be integrated in WHO and continue to work closely with the aforementioned partners.

Stop TB, and Global Drug Facility: In addition to its advocacy role for TB, Stop TB, established in 1998, manages also the Global Drug Facility (GDF, established in 2001), which plays an important role in market shaping and procurement of TB commodities. Given the prime role of the GFATM in terms of medicines procurement and delivery, including for tuberculosis, it makes sense to move the GDF function to the Global Fund/Gavi holding. Stop TB’s important advocacy role can be integrated into WHO.

PMNC- Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health: PMNC is an advocacy alliance bringing together nearly 1500 organizations. Options include incorporating the advocacy platform into WHO, or the GFF mobilizing mechanism.

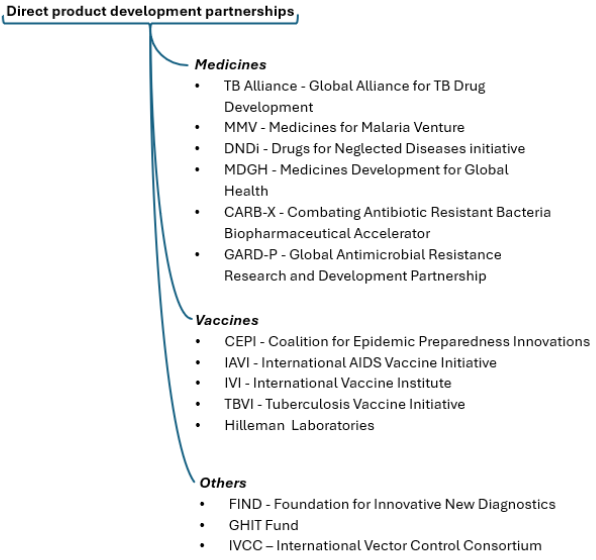

Figure 4. Product Development Partnerships

There is a plethora of global health PDPs, which were established to accelerate product innovation for various infectious diseases, for which there is often a lack of market incentives. Some are pure investors linked to governments (e.g. GHIT Fund in Japan, and RIGHT Fund in Korea), or as a multilateral funding mechanism such as CEPI (Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation). The Gates Foundation is a major funder (and co-founder) of many PDPs. Competition for funds is intense, in an environment of declining investments in infectious diseases product development in general.

Several PDPs have been catalytic in their respective fields, working with industry and academia. After more than two decades of existence, their track record in terms of bringing products to the market is mixed. This is not surprising given the nature of the challenges and long development time in biotech and pharma innovation.

All PDPs are based in the “Global North”, where the agendas are set. However, the PDPs don’t seem to capitalize enough on the growing number of centres of excellence in health R&D across LMIC (except as clinical trial sites), or on initiatives such as the Presidential Initiative for Unlocking the Healthcare Value Chain in Nigeria. Rapidly growing markets, talent availability, and innovation in Africa, Asia and Latin America are additional reasons to broaden geographic scope.

As it is unlikely that classic market forces will consolidate the PDP ecosystem, funders should consider rationalisation and consolidation to increase value for money and impact. Pluralism and competition are important stimulants for innovation. However, in some areas there is a case for maximizing resource utilisation and product development through either mergers and acquisitions, operational alliances or joint activities – as would be the case in the private sector.

There are at least 6 PDPs working in vaccine development, with CEPI holding a special place as a major multilateral funder of epidemic-related R&D. They were mostly created for different pathogens. Today their activities and pathogen selection frequently overlap, leading to competition for funds, partners, and collaborations in the same African countries, with some planning manufacturing in LICs. Together they clearly bring value to the field, in addition to commercial actors, and a few vaccines have been brought to the market thanks to their efforts. However, none have sufficient critical mass.

One option is creating a holding company to rationalise structures, integrate platforms, optimize development, and trial sites, and integrate functions like advocacy, HR, procurement, whilst still continuing specific activities. A risk is the creation of over-complex bureaucracies.

In any case, there should be greater involvement and ownership of centers of excellence in LMICs, including in governance, strategy and execution.

While the agendas proposed may seem overwhelming, failing to address the need for transformative change risks an even greater paralysis in the years ahead. The following 10 considerations should guide reform initiatives:

1.It is more productive to be proactive, rather than to wait for an acute crisis forcing improvised solutions – or hoping for a return to generous international funding. Transitions and consolidations must be managed responsibly with a clear focus on the core needs of countries and communities, while ensuring that unavoidable costs of change are carefully contained.

2. Co-creation with all main constituencies should be the norm, and we welcome the growing number of initiatives, particularly those led by the Global South, such as the Accra Reset and the ALM. The Wellcome Trust has initiated a series of regional reflections, the European Commission is convening a “Donor Reflection Process on Global Health Reform”, and a “Future of Development Cooperation Coalition” was launched recently. The engagement of all public and private constituencies will be needed, including the USA as it remains a major actor in global health. In the past, nearly all GHIs were largely created by donors—with UNAIDS as a notable exception—but today alliances should span several continents given the global nature of the issues, as advocated by the Accra Reset. Soon the time for reflection and often overly academic proposals should make way for political and institutional action.

3.Setting a clear time frame will be essential to achieving results. Whereas 2026 can be the year of planning and consultations, the aim should be to fully implement reform in 2027 and 2028. We assume there will be broad theoretical agreement on most principles elaborated here, but translating them into new structures, and above all, practices, will require relevant coalitions of stakeholders, as well as strong political backing. Timing is often crucial for change, with some opportunities occurring when there is a change of leadership (e.g. coming up at the Global Fund and WHO), besides the ongoing financial pressure. A logical first step is to establish task forces of interested parties to formulate proposals, and initiate negotiations within an agreed time frame. A real risk is that a wave of reform efforts will give rise to an outbreak of more meetings and conferences with little action.

4. Consider carefully the legitimacy and governance of such reforms. A combination of “coalitions of the willing,” global and regional political entities, and governing boards, with co-creation by various types of partners, is likely to be more effective than governing boards of the institutions concerned. Structural changes in multilateral organisations coming from within are notoriously difficult and rare. It is often donors who maintain the fragmentation of the ecosystem through their support, and sometimes inconsistent positions in different institutions. Ultimately, endorsement by external stakeholders and political entities such as the UN, G20, African Union, and other regional political bodies, will be crucial.

One of the major criticisms of GHIs (and the multilateral system as a whole) has been that their governance has not evolved with the times. Governance, accountability and transparency should be much stronger than is currently the case. The process must also be more inclusive of the Global South, and ideally involve representation of all relevant constituencies, including civil society and the private sector– as already practiced in a number of organisations today.

5. Prioritising and using the momentum for change in a specific institution or cluster is more realistic than trying to change the whole ecosystem, even if the same parties are involved in multiple GHIs. We realize that at least parts of our proposals are not novel, and several have been attempted previously, often with limited success. However, the current momentum for change presents a new opportunity.

6. A reformed global health ecosystem can only support better health outcomes as long as domestic investment in health becomes a national priority in all countries. This is challenging in countries with a huge debt burden and will require innovative solutions besides the classic government financing .

7. Continuity of essential functions and activities must be assured during this transition period, particularly in humanitarian crises and epidemics, and in essential health interventions such as immunisation, maternal and child health, and HIV, TB and malaria control. This will require continued funding, and uninterrupted operational capacity of relevant institutions.

8. There are obviously trade-offs to address. While more cost-effective and country-owned consolidations is a priority, we should not neglect the long term need for support for specific countries, humanitarian responses, pandemic preparedness, and for innovation development and access.

9. Each institution has a genuine raison d’etre, and committed constituencies and supporters. There will undoubtedly be lobbying against change– as is already happening around the proposed sunset of UNAIDS. It will be important to both engage with these constituencies, but also to resist being driven by lobbying and specific interests.

10. In each case the balance between global and regional mechanisms should be considered, as well as potential reforms at regional levels. The PAHO revolving fund or the recently launched African Medicines Agency (AMA) and the African Pooled Procurement Mechanism (APPM), provide foundations for regional approaches.

Finally, are such reforms feasible, not just needed? There was equal scepticism when the current GHIs were launched, but in a short time consensus was reached. Rather than dwelling on the risks - both real and perceived- we must focus on solid solutions.

Within three years a very different model of global health ecosystem should be operational - one that empowers countries to build sustainable health infrastructure, confront security threats, and share innovation across borders. The challenge is immense, but the opportunity is greater: to create a more resilient, and more just global health order.

We acknowledge with thanks the excellent research and writing support from Sarah Curran and Hannah Herzig, and inputs from Corine Karema and Mayowa Alade, as well as the numerous conversations with stakeholders around the world.

@muhammadpate, @DonaldKaberuka, peter.piot@lshtm.ac.uk

1. Presidency Communications. (2025, August 5). The Accra Initiative: African health sovereignty in a reimagined global health architecture. Accra, Ghana,

2. Presidency Communications. (2025, October 1). President Mahama & global leaders launch the Accra Reset at UNGA 2025. Accra, Ghana.

3. Gates Foundation. (2024). Goalkeepers report 2024: The race to nourish a warming world. https://www.gatesfoundation.org/goalkeepers/report/2024-report/

4. The Lancet. (2025, October). The Global Burden of Disease Study 2023 (194 pp.). https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(25)01186-9/fulltext

5. Apeagyei, A. E., Bisignana, C., Elliott, H., et al. (2025). Tracking development assistance for health, 1990–2030: Historical trends, recent cuts, and outlooks. The Lancet, 406, 337–348.

6. Cavalcanti, D. M., et al. (2024). Evaluating the impact of two decades of USAID interventions and projecting the effects of defunding on mortality up to 2030: A retrospective impact evaluation and forecasting analysis. The Lancet, 406(10500), 283–294. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(25)01186-9/fulltext

7. World Bank. (2018). World Bank Group support to health services: Achievements and challenges. Independent Evaluation Group. Washington, DC: World Bank.

8. Center for Healthy Development. (2025). Taking stock of development assistance for health (DAH) in the 21st century: Renewing our commitment.

9. Rasanathan, K., Cloete, K., Gitahi, et al. (2025). Functions of the global health system in a new era. Nature Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03936-9

10. Kyobutungi, K. (2025). Rethinking the global health architecture in service of Africa’s needs: A perspective from the Africa Region. Wellcome, 13.

11. U.S. Department of State. (2025, September). America First Global Health Strategy (36 pp.). Washington, DC. https://www.state.gov/america-first-global-health-strategy

12. Rao, N., Tomar, P., Kickbusch, I., et al. (2025). Shifting power dynamics in global health governance: A challenge and an opportunity for Asia and the Global South. VeriXiv. https://doi.org/10.12688/verixiv.1783.1

13. Lastuka, A., Breshock, M. R., Hay, S. I., et al. (2025). Global, regional, and national health-care inefficiency and associated factors in 201 countries, 1995–2022: A stochastic frontier meta-analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. The Lancet. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(25)00178-0

14. Future of Global Health Initiatives. (2023, December 12). The Lusaka agenda: Conclusions of the Future of Global Health Initiatives process. https://futureofghis.org/final-outputs/lusaka-agenda/

15. African Union Development Agency (NEPAD). (2023). African Leadership Meeting – Investing in Health Declaration briefing paper. https://www.nepad.org/publication/african-leadership-meeting-investing-health-declaration-briefing-paper

16. Africa CDC. (2022). Call to action: Africa’s new public health order. https://africacdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Call-to-Action-NPHO-Final-CTA-20-Sep-Edited.pdf

17. Nishtar, S. (2025). The Gavi leap: Radical transformation for a new global health architecture. The Lancet, 405, 2112–2113. https://www.gavi.org/news/media-room/gavi-statement-global-health-architecture

18. Sands P. (2025), Transforming global health to maximize impact and accelerate self-reliance. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/peter.sands/2025/11/13/transforming-global-health-to-maximize-impact-and-accelerate-self-reliance/

19. Drake, T., Regan, L., & Baker, P. (2023, February). Reimagining global health financing: How refocusing health aid at the margin could strengthen health systems and futureproof aid financial flows (Policy Paper No. 285). Center for Global Development. Washington, DC.

20.World Health Organization. (2025). Strengthening health financing globally (WHA78.12). Seventy-eighth World Health Assembly. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA78/A78_R12-en.pdf

21. Sevilla Platform for Action. (2025, June 30–July 3). 4th International Conference on Financing for Development.

United Nations. (2025, September). UN80 Initiative: Shifting paradigms – United to deliver. Report of the Secretary-General. Workstream 3: Changing structures and realigning programmes (45 pp.). New York.

Kickbusch, I., Kazatchkine, M., & Piot, P. (2025, July 31). Rethinking the role of WHO in a transformed global health order. Geneva Health Files.